A practitioner is a manager of a group home. The practitioner encourages the staff to assist interested residents in connecting to local religious congregations. What psychiatric rehabilitation principle is the practitioner implementing?

Services should be normalized and incorporate natural supports.

Service systems should be accountable to the individuals using them.

Services should build on the assets and strengths of the individuals using them.

Services should be flexible and well-coordinated.

This question aligns with Domain III: Community Integration, which focuses on connecting individuals to community resources and natural supports to enhance integration and recovery. The CPRP Exam Blueprint emphasizes “incorporating natural supports, such as religious or community organizations, to promote normalized community participation.” Connecting residents to local religious congregations leverages community-based natural supports, aligning with psychiatric rehabilitation principles.

Option A: Encouraging connections to religious congregations reflects the principle of normalizing services and incorporating natural supports. Religious congregations are community-based resources that provide social, spiritual, and practical support, fostering integration in a normalized setting, which is a core tenet of psychiatric rehabilitation.

Option B: Accountability to individuals is important but not directly related to connecting residents to religious congregations, which focuses on community engagement rather than system oversight.

Option C: Building on assets and strengths is relevant but less specific to this scenario, as the focus is on connecting to external community supports rather than individual strengths.

Option D: Flexibility and coordination are systems-level principles but do not directly describe the act of leveraging natural supports like religious congregations.

Extract from CPRP Exam Blueprint (Domain III: Community Integration):

“Tasks include: 2. Promoting community integration through connections to natural supports, such as religious or social organizations. 3. Providing normalized services to enhance community participation.”

What are the components of a psychiatric rehabilitation diagnosis?

Resource assessment, functional assessment, and an overall rehabilitation goal

Social skill assessment, psychiatric diagnosis, and an overall rehabilitation goal

Readiness assessment, skill management, and resource evaluation

Functional assessment, diagnostic assessment, and skill programming

A psychiatric rehabilitation diagnosis focuses on identifying an individual’s strengths, needs, and aspirations to guide recovery-oriented planning, distinct from a clinical diagnosis. The CPRP Exam Blueprint (Domain IV: Assessment, Planning, and Outcomes) outlines the components as a functional assessment (to identify strengths and deficits), a resource assessment (to evaluate available supports), and an overall rehabilitation goal (to set a person-centered objective) (Task IV.A.1: "Conduct functional assessments to identify individual goals and strengths" and Task IV.A.3: "Assess available resources to support goal attainment"). Option A (resource assessment, functional assessment, and an overall rehabilitation goal) aligns with this framework, capturing the holistic, recovery-focused approach of psychiatric rehabilitation.

Option B (social skill assessment, psychiatric diagnosis, rehabilitation goal) is incorrect, as psychiatric diagnosis is clinical and not part of rehabilitation diagnosis, and social skills are a subset of functional assessment. Option C (readiness assessment, skill management, resource evaluation) mixes assessment and intervention terms, missing the goal component. Option D (functional assessment, diagnostic assessment, skill programming) includes clinical diagnostic assessment, which is not relevant, and skill programming is an intervention, not a diagnostic component. The PRA Study Guide details these components as essential for rehabilitation planning, supporting Option A.

An individual with a psychiatric disability complains that her medication is making her too drowsy, even though it stops the distressing voices she hears. When using self-disclosure, the practitioner should:

Describe a time when he injured his back and had to work closely with his doctor to get the medicine adjusted so that it did not make him dizzy.

Talk about the time he stopped taking antibiotics without completing the entire course and then had a recurrence of his infection.

Share that he always takes his medications exactly as prescribed because he feels that his doctor knows what is best for him.

Talk about his family’s demands upon him and how difficult it is for him to cope.

This question falls under Domain I: Interpersonal Competencies, which emphasizes person-centered communication, including the appropriate use of self-disclosure to build therapeutic relationships. The CPRP Exam Blueprint specifies that self-disclosure should be “relevant, purposeful, and aimed at fostering hope, empathy, or collaboration, while maintaining professional boundaries.” In this scenario, the individual is struggling with medication side effects (drowsiness), and the practitioner’s self-disclosure should relate to this experience to validate her concerns and encourage collaboration with healthcare providers.

Option A: Describing a personal experience of adjusting medication with a doctor due to side effects (dizziness) is relevant to the individual’s situation. It validates her experience, models collaboration with a healthcare provider, and fosters hope that side effects can be managed, aligning with recovery-oriented communication.

Option B: Discussing stopping antibiotics is unrelated to psychiatric medication or side effects and focuses on non-adherence, which could imply judgment and is not therapeutic in this context.

Option C: Sharing strict adherence to medication due to trust in a doctor may dismiss the individual’s valid concerns about side effects, potentially alienating her and undermining person-centered communication.

Option D: Talking about family demands is irrelevant to the individual’s medication concerns and risks shifting focus to the practitioner’s personal issues, violating professional boundaries.

Extract from CPRP Exam Blueprint (Domain I: Interpersonal Competencies):

“Tasks include: 1. Establishing and maintaining a therapeutic relationship with individuals. 2. Using self-disclosure purposefully to foster hope, empathy, or collaboration, while maintaining professional boundaries.”

Which of the following factors BEST contributes to wellness among individuals with psychiatric disabilities?

Symptom self-management.

Utilizing natural supports and alternative healing programs.

Regular visits to medical specialists.

A self-defined balance of healthy habits and behaviors.

Wellness in psychiatric rehabilitation is a holistic, person-centered concept that encompasses physical, emotional, and social well-being, driven by individual choice. The CPRP Exam Blueprint (Domain VII: Supporting Health & Wellness) emphasizes empowering individuals to define and pursue their own wellness through balanced, healthy habits (Task VII.A.1: "Promote holistic wellness, including self-defined healthy habits and behaviors"). Option D (a self-defined balance of healthy habits and behaviors) aligns with this, as it reflects the individual’s autonomy in choosing practices—such as exercise, nutrition, or social activities—that promote wellness tailored to their needs and preferences.

Option A (symptom self-management) is important but narrower, focusing on clinical aspects rather than holistic wellness. Option B (natural supports and alternative healing) is a component but less comprehensive than self-defined habits, which encompass a broader range of wellness practices. Option C (regular visits to medical specialists) is a clinical intervention, not the primary driver of wellness, which prioritizes self-directed health. The PRA Study Guide, referencing SAMHSA’s Eight Dimensions of Wellness, underscores self-defined healthy habits as central to wellness, supporting Option D.

An individual and her practitioner are in a treatment team meeting in which potential options for the individual are being discussed. The practitioner’s priority is to advocate for an option that is:

Conducive to the individual’s stability.

Least restrictive.

Financially realistic.

Consistent with the individual’s wishes.

This question pertains to Domain II: Professional Role Competencies, which emphasizes advocacy and person-centered practice. The CPRP Exam Blueprint and PRA Code of Ethics state that “practitioners prioritize advocating for options that align with the individual’s preferences and wishes, as this respects autonomy and promotes recovery.” While stability, restrictiveness, and financial considerations are important, the individual’s wishes are the primary focus in a recovery-oriented approach.

Option D: Advocating for an option consistent with the individual’s wishes prioritizes her autonomy and self-determination, which are core to psychiatric rehabilitation. This ensures the treatment plan reflects her values and goals, fostering engagement and recovery.

Option A: Stability is important but secondary to the individual’s preferences, as imposing stability-focused options may undermine autonomy.

Option B: The least restrictive option is a principle in mental health law but is not the primary focus in a treatment team meeting, where the individual’s wishes take precedence.

Option C: Financial realism is a practical consideration but not the practitioner’s priority over respecting the individual’s preferences.

Extract from CPRP Exam Blueprint (Domain II: Professional Role Competencies):

“Tasks include: 2. Advocating for options that align with the individual’s preferences and wishes to promote autonomy and recovery.”

Sharing personal recovery stories is important because they

demonstrate that recovery is possible.

reduce the need for formal interventions.

reduce the storyteller’s symptoms.

make services more person-centered.

Sharing personal recovery stories is a powerful strategy in psychiatric rehabilitation to inspire hope and motivate others. The CPRP Exam Blueprint (Domain V: Strategies for Facilitating Recovery) emphasizes the use of recovery stories, often through peer support, to illustrate that recovery is achievable, fostering hope and engagement in recovery processes (Task V.B.3: "Utilize peer support to promote recovery and rehabilitation goals"). Option A (demonstrate that recovery is possible) aligns with this, as stories from individuals with lived experience show tangible examples of overcoming challenges, encouraging others to pursue their own recovery goals.

Option B (reduce the need for formal interventions) is inaccurate, as stories complement, not replace, interventions. Option C (reduce the storyteller’s symptoms) may be a secondary benefit but is not the primary purpose. Option D (make services more person-centered) is indirectly related but less specific, as stories primarily inspire rather than reshape service delivery. The PRA Study Guide underscores recovery stories as a tool for hope and possibility, supporting Option A.

Literature suggests that bolstering the social support network of people who have been diagnosed with schizophrenia can MOST importantly improve their

social skills.

ability to work.

sense of well-being.

symptomatology.

Social support networks are critical for enhancing wellness among individuals with schizophrenia, as they provide emotional, practical, and social resources that foster recovery. The CPRP Exam Blueprint (Domain VII: Supporting Health & Wellness) emphasizes the role of social connections in promoting overall well-being (Task VII.B.1: "Support the development of social and interpersonal skills to enhance wellness"). Option C (sense of well-being) aligns with this, as literature consistently shows that strong social support networks improve emotional and psychological well-being by reducing isolation, enhancing self-esteem, and providing a sense of belonging, which are particularly vital for individuals with schizophrenia.

Option A (social skills) may improve indirectly through social engagement, but it is not the primary outcome, as skills are a means to well-being, not the end goal. Option B (ability to work) is a secondary benefit, as employment depends on multiple factors beyond social support (Domain III). Option D (symptomatology) may see some improvement, but well-being is a broader, more direct outcome of social support, as symptom reduction is not guaranteed by social networks alone. The PRA Study Guide, referencing recovery-oriented research, highlights social support as a key driver of well-being, supporting Option C.

A practitioner working in a residential program often has to intervene in conflicts among housemates living in the facility. Which of the following strategies would the practitioner use?

Prescribe a time-out for the individuals in conflict.

Recommend the housemates contact their case managers to report the conflict.

Schedule a time for each individual to discuss the problem privately.

Help housemates distinguish the individuals from the problem.

Conflict resolution is an essential interpersonal competency for practitioners in psychiatric rehabilitation, particularly in settings like residential programs where interpersonal dynamics are common. The CPRP Exam Blueprint (Domain I: Interpersonal Competencies) emphasizes using collaborative, person-centered strategies to manage conflicts (Task I.B.2: "Facilitate conflict resolution using recovery-oriented approaches"). Option D (help housemates distinguish the individuals from the problem) aligns with this task by employing a recovery-oriented technique, such as narrative or solution-focused approaches, that externalizes the problem (e.g., “the conflict is the issue, not the people”). This fosters collaboration and reduces personal blame, promoting constructive dialogue.

Option A (prescribe a time-out) is authoritarian and not recovery-oriented, as it does not empower individuals to resolve the conflict. Option B (recommend contacting case managers) deflects responsibility and does not address the conflict directly, missing an opportunity for skill-building. Option C (discuss the problem privately) may be part of a process but is less effective than Option D, as it does not directly facilitate group resolution or teach conflict management skills. The PRA Study Guide highlights externalizing problems as a best practice in conflict resolution, supporting Option D.

One of the components of wellness is

compliance with medication.

avoidance of stress.

purpose in life.

absence of illness.

Wellness in psychiatric rehabilitation is a multidimensional concept that encompasses physical, mental, emotional, and social well-being, guided by recovery principles. The CPRP Exam Blueprint (Domain VII: Supporting Health & Wellness) includes supporting individuals in finding meaning and purpose as a key component of wellness (Task VII.A.1: "Promote holistic wellness, including purpose and meaning in life"). Option C (purpose in life) aligns with this task, as having a sense of purpose—through roles, goals, or activities—is a recognized dimension of wellness that fosters resilience and recovery.

Option A (compliance with medication) is a clinical strategy, not a core component of wellness, though it may support health (Domain VII). Option B (avoidance of stress) is impractical and not explicitly listed as a wellness dimension, as wellness involves managing, not eliminating, stress. Option D (absence of illness) is inaccurate, as wellness is not defined by the absence of illness but by positive attributes like purpose, relationships, and self-management, even in the presence of symptoms. The PRA Study Guide, referencing models like SAMHSA’s Eight Dimensions of Wellness, includes purpose as a key element, supporting Option C.

Which of the following best reflects key elements of recovery?

The process of readjusting attitudes, feelings, and beliefs about self and others that addresses life goals

The process of redefining attitudes, feelings, and beliefs that takes place within a defined period of time

The linear process of examining attitudes, feelings, and beliefs that moves toward a defined goal

The personal process of adjusting attitudes, feelings, and beliefs that is defined by a particular diagnosis of illness

This question falls under Domain V: Strategies for Facilitating Recovery, which emphasizes the principles of recovery-oriented psychiatric rehabilitation, including hope, self-determination, and personal growth. The CPRP Exam Blueprint defines recovery as “a personal, non-linear process of readjusting attitudes, feelings, and beliefs to pursue meaningful life goals, regardless of the presence of mental illness.” The question tests the candidate’s understanding of recovery as a holistic, individualized process focused on life goals rather than a time-bound, linear, or diagnosis-driven framework.

Option A: This option accurately describes recovery as a process of readjusting attitudes, feelings, and beliefs about self and others while focusing on life goals. It captures the individualized, goal-oriented nature of recovery and aligns with the PRA’s recovery model, which emphasizes hope, empowerment, and community integration.

Option B: Specifying a “defined period of time” contradicts the non-linear, ongoing nature of recovery, which varies for each individual and is not time-bound.

Option C: Describing recovery as a “linear process” is inaccurate, as recovery is recognized as non-linear, with ups and downs, rather than a straightforward progression toward a single goal.

Option D: Tying recovery to a “particular diagnosis of illness” is incorrect, as recovery is not defined by a diagnosis but by the individual’s personal journey toward meaning and purpose, regardless of symptoms.

Extract from CPRP Exam Blueprint (Domain V: Strategies for Facilitating Recovery):

“Tasks include: 1. Promoting recovery-oriented principles, including hope, self-determination, and personal responsibility. 2. Supporting individuals in redefining attitudes, feelings, and beliefs to pursue meaningful life goals.”

One of the BEST ways to reduce stigma is through

sensitivity training workshops.

public awareness demonstrations.

interaction with diverse individuals.

research of oppressed populations.

Reducing stigma toward individuals with psychiatric disabilities requires strategies that challenge stereotypes and foster understanding. The CPRP Exam Blueprint (Domain VI: Systems Competencies) highlights promoting direct interaction with individuals with lived experience as a key method to reduce stigma, as it humanizes mental health conditions and counters misconceptions (Task VI.A.3: "Advocate for stigma reduction through community engagement"). Option C (interaction with diverse individuals) aligns with this, as personal contact—such as through peer-led programs, community events, or storytelling—has been shown to effectively decrease prejudice and promote empathy among the public.

Option A (sensitivity training workshops) is useful but less impactful than direct interaction, which provides lived experience. Option B (public awareness demonstrations) raises visibility but may not foster deep understanding like personal contact. Option D (research of oppressed populations) informs policy but does not directly engage communities to reduce stigma. The PRA Study Guide, referencing contact-based stigma reduction strategies, supports Option C as a best practice.

Wellness Recovery Action Plan (WRAP) is most useful for which of the following?

Adapting 12-step programs to address symptoms.

Providing tools to handle stress.

Increasing adherence to treatment.

Replacing advance directives.

The Wellness Recovery Action Plan (WRAP), developed by Mary Ellen Copeland, is a self-directed, recovery-oriented framework that empowers individuals to manage their mental health and wellness. The CPRP Exam Blueprint (Domain V: Strategies for Facilitating Recovery) highlights WRAP as a tool for developing self-management skills, particularly for managing stress and preventing crises (Task V.B.2: "Facilitate the development of self-management skills"). Option B (providing tools to handle stress) aligns with WRAP’s core components, which include identifying triggers, creating a wellness toolkit (e.g., coping strategies like mindfulness or exercise), and developing action plans to manage stress and symptoms effectively.

Option A (adapting 12-step programs) is incorrect, as WRAP is a distinct, personalized recovery model, not an adaptation of 12-step programs, which focus on addiction recovery. Option C (increasing adherence to treatment) may be an indirect benefit but is not WRAP’s primary purpose, which emphasizes self-empowerment over compliance. Option D (replacing advance directives) is incorrect, as WRAP complements, but does not replace, legal documents like advance directives, which are addressed separately (Task V.C.3). The PRA Study Guide emphasizes WRAP’s role in fostering resilience and stress management, supporting Option B.

Functional assessment includes which of the following?

Assessment of activities of daily living needs for future roles

Assessment of current functional successes and challenges

Assessment of educational successes and goals in life

Assessment of past functional successes in all domains

A functional assessment in psychiatric rehabilitation evaluates an individual’s current abilities and barriers to inform recovery-oriented planning. The CPRP Exam Blueprint (Domain IV: Assessment, Planning, and Outcomes) defines functional assessment as identifying current functional successes (strengths) and challenges (deficits) across domains like self-care, social skills, or employment to guide goal-setting (Task IV.A.1: "Conduct functional assessments to identify individual goals and strengths"). Option B (assessment of current functional successes and challenges) aligns with this, as it focuses on the individual’s present capabilities and limitations to develop relevant, person-centered interventions.

Option A (activities of daily living for future roles) is narrower and future-focused, not capturing the full scope of current functioning. Option C (educational successes and goals) is too specific, as functional assessment spans multiple domains. Option D (past functional successes) is retrospective and less relevant than current functioning for planning. The PRA Study Guide emphasizes assessing current strengths and challenges as the core of functional assessment, supporting Option B.

A practitioner is providing service to an individual who discusses experiences of repeated trauma. The practitioner would

provide cognitive behavioral treatment.

attend training in trauma-informed care.

conduct a functional assessment.

explore resources for trauma-specific care.

When an individual discloses experiences of repeated trauma, practitioners must respond with interpersonal competencies that prioritize sensitivity, ethical practice, and appropriate referrals. The CPRP Exam Blueprint (Domain I: Interpersonal Competencies) emphasizes identifying when specialized services are needed and connecting individuals to appropriate resources (Task I.C.2: "Identify and refer individuals to appropriate services based on their needs"). Option D (explore resources for trauma-specific care) aligns with this, as trauma-specific care (e.g., trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy or EMDR) requires specialized expertise, and the practitioner’s role is to facilitate access to qualified professionals or programs tailored to trauma recovery.

Option A (provide cognitive behavioral treatment) is outside the scope of most psychiatric rehabilitation practitioners, who are not typically licensed to deliver specialized therapies. Option B (attend training in trauma-informed care) is valuable for professional development but does not directly address the individual’s immediate need for trauma-specific intervention. Option C (conduct a functional assessment) may be part of planning but is not the most immediate response to trauma disclosures. The PRA Study Guide and Code of Ethics emphasize referring trauma-related issues to specialists, supporting Option D.

The practitioner is meeting with a deaf individual with a psychiatric disability who uses a sign language interpreter. When meeting with the individual, the practitioner should communicate:

Speak alternately to the individual and to the interpreter.

Directly to the individual.

Slowly and distinctly so the interpreter can keep up.

Directly to the interpreter.

This question aligns with Domain I: Interpersonal Competencies, which focuses on effective, person-centered communication and cultural competence, including accommodating individuals with disabilities. The CPRP Exam Blueprint highlights that practitioners must “adapt communication strategies to meet the needs of individuals with diverse abilities, including those with sensory disabilities.” When working with a deaf individual using a sign language interpreter, best practice involves communicating directly with the individual to maintain a person-centered, respectful interaction.

Option B: Communicating directly to the individual (e.g., making eye contact and addressing them, not the interpreter) respects their autonomy and ensures the interaction remains person-centered. The interpreter facilitates communication by translating, but the practitioner’s focus should be on the individual, as this aligns with recovery-oriented principles and cultural competence.

Option A: Speaking alternately to the individual and interpreter disrupts the flow of communication and may confuse the interaction, undermining the individual’s role in the conversation.

Option C: Speaking slowly and distinctly is unnecessary unless requested by the interpreter, as professional interpreters are trained to keep up with normal speech. This option also shifts focus to the interpreter’s needs rather than the individual’s.

Option D: Communicating directly to the interpreter excludes the individual from the interaction, which is disrespectful and not person-centered. It treats the interpreter as the primary recipient rather than a facilitator.

Extract from CPRP Exam Blueprint (Domain I: Interpersonal Competencies):

“Tasks include: 4. Adapting communication strategies to meet the needs of individuals with diverse abilities and cultural backgrounds. 5. Demonstrating cultural competence in all interactions.”

Readiness in rehabilitation refers to how

developed an individual’s skills are.

likely an individual is to follow through.

prepared an individual is to set a goal.

likely an individual is to succeed or fail.

Rehabilitation readiness assesses an individual’s preparedness to engage in goal-setting and pursue recovery-oriented objectives. The CPRP Exam Blueprint (Domain IV: Assessment, Planning, and Outcomes) defines readiness as the individual’s capacity and motivation to identify and work toward specific goals (Task IV.A.2: "Assess individual’s stage of change and readiness for goal-setting"). Option C (prepared an individual is to set a goal) aligns with this, as readiness involves evaluating factors like hope, confidence, and willingness to define achievable rehabilitation goals, such as employment or education.

Option A (developed skills) focuses on abilities, not readiness, which is about motivation and mindset. Option B (likelihood to follow through) is an outcome of readiness, not its definition. Option D (likelihood to succeed or fail) is overly outcome-focused and not the primary focus of readiness assessment. The PRA Study Guide describes readiness as the precursor to effective goal-setting, supporting Option C.

An Illness Management group should include which of the following areas?

Psychoeducation, conflict resolution, psychopharmacology, and coping skills training

Behavioral tailoring, conflict resolution, and psychopharmacology

Medication adherence, relapse prevention, and social skills

Psychoeducation, behavioral tailoring, relapse prevention, and coping skills training

This question pertains to Domain V: Strategies for Facilitating Recovery, which includes implementing evidence-based practices like Illness Management and Recovery (IMR). The CPRP Exam Blueprint specifies that IMR groups focus on “psychoeducation, behavioral tailoring, relapse prevention, and coping skills training to empower individuals to manage their mental health.” The question tests knowledge of the core components of an IMR group, an evidence-based practice in psychiatric rehabilitation.

Option D: This option lists psychoeducation (education about mental health), behavioral tailoring (strategies to incorporate medication or treatment into daily routines), relapse prevention (identifying and managing early warning signs), and coping skills training (techniques to manage symptoms). These are the core components of IMR, as outlined in PRA study materials and IMR protocols.

Option A: Includes conflict resolution, which is not a standard component of IMR, and psychopharmacology, which is too specific (IMR covers medication management broadly, not detailed pharmacology).

Option B: Includes conflict resolution, which is not part of IMR, and omits key components like psychoeducation and coping skills training.

Option C: Includes social skills, which is not a core IMR component (though related to other interventions), and omits psychoeducation and behavioral tailoring, making it incomplete.

Extract from CPRP Exam Blueprint (Domain V: Strategies for Facilitating Recovery):

“Tasks include: 3. Implementing evidence-based practices, such as Illness Management and Recovery, which include psychoeducation, behavioral tailoring, relapse prevention, and coping skills training.”

When integrating peer support services into their program, an agency needs to consider potential issues with

absenteeism and utilization of benefits.

power and boundaries.

medication and symptoms.

stigma and confidentiality.

Integrating peer support services involves leveraging individuals with lived experience to support others, but it requires careful management of professional dynamics. The CPRP Exam Blueprint (Domain VI: Systems Competencies) emphasizes establishing clear roles and boundaries to ensure effective peer integration (Task VI.C.2: "Support the integration of peer services within program structures"). Option B (power and boundaries) aligns with this, as peer supporters, who share personal experiences, may face challenges with maintaining professional boundaries or navigating power dynamics (e.g., avoiding over-identification or dual relationships), which agencies must address through training and policies.

Option A (absenteeism and benefits) is a general employment concern, not specific to peer support. Option C (medication and symptoms) is a clinical issue, not a primary integration concern. Option D (stigma and confidentiality) is relevant but secondary to boundary issues, which are more critical for peer role clarity. The PRA Study Guide highlights power and boundary management as key for peer support integration, supporting Option B.

An individual describes a history of sexual abuse to his practitioner. The individual believes that this is causing him to have difficulty being intimate with his partner. After listening to his concerns, the practitioner’s next BEST response is to

assist him in developing action steps.

assist him in developing a WRAP plan.

refer him and his partner to a support group.

refer him and his partner to a qualified therapist.

Addressing sensitive disclosures, such as a history of sexual abuse, requires interpersonal competencies that prioritize empathy, ethical practice, and appropriate referrals. The CPRP Exam Blueprint (Domain I: Interpersonal Competencies) emphasizes recognizing when issues require specialized intervention and making appropriate referrals (Task I.C.2: "Identify and refer individuals to appropriate services based on their needs"). Option D (refer him and his partner to a qualified therapist) is the best response, as a history of sexual abuse and its impact on intimacy are complex issues that typically require specialized therapeutic intervention, such as trauma-focused therapy or couples counseling, to address underlying trauma and relational dynamics effectively.

Option A (developing action steps) is premature without professional therapeutic support to address the trauma. Option B (developing a WRAP plan) is inappropriate, as WRAP focuses on self-management of mental health, not trauma-specific issues (Domain V). Option C (referring to a support group) may be a supplementary step but is less immediate and targeted than therapy for addressing trauma and intimacy concerns. The PRA Code of Ethics and Study Guide emphasize referring to qualified professionals for issues outside the practitioner’s scope, supporting Option D.

An individual with a psychiatric disability tells her job coach that she has been written up for the third time for being late and is worried about losing her job. She is struggling to wake up on time due to medication side effects. The best course of action for the job coach is to:

Help her explore alternative employment options.

Refer her to a work adjustment program to practice being on time.

Schedule transportation so she can be on time.

Discuss the option of requesting accommodations with her.

This question aligns with Domain III: Community Integration, which focuses on supporting individuals to maintain employment through strategies like workplace accommodations. The CPRP Exam Blueprint emphasizes “assisting individuals to request reasonable accommodations to address disability-related barriers, such as medication side effects, to sustain community employment.” The individual’s lateness is due to medication side effects, and accommodations can address this barrier while preserving her job.

Option D: Discussing the option of requesting accommodations (e.g., a later start time or flexible schedule) is the best course of action, as it directly addresses the medication side effects causing lateness. This approach, supported by laws like the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), empowers the individual to maintain her job while managing her disability, aligning with recovery-oriented employment support.

Option A: Exploring alternative employment is premature and unnecessary, as accommodations may resolve the issue without requiring a job change, which could disrupt stability.

Option B: A work adjustment program focuses on general work skills, not specific barriers like medication side effects, and may not address the immediate risk of job loss.

Option C: Scheduling transportation does not address the root cause (difficulty waking up due to medication), making it an ineffective solution.

Extract from CPRP Exam Blueprint (Domain III: Community Integration):

“Tasks include: 2. Supporting individuals in maintaining employment through strategies like reasonable accommodations to address disability-related barriers. 3. Promoting self-advocacy in workplace settings.”

A practitioner and an individual have spent months developing a plan to achieve the individual’s goal to "stop using drugs." On the day the individual has identified as the start date, he decides that he no longer wants to quit. This is an example of

resistance.

denial.

withdrawal.

substitution.

The individual’s decision to abandon his goal to stop using drugs on the planned start date reflects a shift in motivation, often seen in the context of change processes. The CPRP Exam Blueprint (Domain IV: Assessment, Planning, and Outcomes) addresses assessing readiness and responses to change, noting that resistance can manifest as reluctance or reversal of commitment, particularly when facing the reality of action (Task IV.A.2: "Assess individual’s stage of change and readiness for goal-setting"). Option A (resistance) aligns with this, as the individual’s sudden decision not to quit suggests ambivalence or fear of change, common in the transition from planning to action in the Stages of Change model (e.g., moving from preparation to contemplation or pre-contemplation).

Option B (denial) implies rejecting the problem entirely, which is not indicated, as he previously acknowledged the goal. Option C (withdrawal) refers to physical or emotional retreat, not a change in goal commitment. Option D (substitution) involves replacing one behavior with another, which is not described. The PRA Study Guide identifies resistance as a common response to change, supporting Option A.

When working with an individual who has both substance abuse issues and a mood disorder, the practitioner has determined that the individual is in the pre-contemplative stage of change in regard to his substance use. The practitioner’s interventions should focus on

teaching the skill of saying no to alcohol.

identifying triggers that lead to drinking.

establishing a goal to decrease alcohol use.

developing a trusting relationship.

In the pre-contemplative stage of change, individuals are not yet considering changing their behavior (e.g., substance use) and may deny or minimize the problem. The CPRP Exam Blueprint (Domain I: Interpersonal Competencies) emphasizes building trust and rapport with individuals in early stages of change to foster engagement and openness to future interventions (Task I.B.3: "Adapt communication strategies to build trust and engagement"). Option D (developing a trusting relationship) aligns with this, as establishing trust through empathetic, non-judgmental interactions is critical to help the individual feel safe and eventually consider change, particularly for someone with co-occurring substance abuse and mood disorders.

Option A (teaching the skill of saying no) is action-oriented and premature for pre-contemplation. Option B (identifying triggers) is relevant in later stages, like contemplation or preparation. Option C (establishing a goal to decrease use) assumes readiness not present in pre-contemplation. The PRA Study Guide, referencing the Stages of Change model, highlights trust-building as the primary focus for pre-contemplative individuals, supporting Option D.

When teaching a skill, role playing should usually be done after

modeling the skill.

practicing the skill.

trying the skill for the first time.

describing how to do the skill.

Teaching skills in psychiatric rehabilitation follows a structured, evidence-based process to ensure effective learning. The CPRP Exam Blueprint (Domain V: Strategies for Facilitating Recovery) outlines skill teaching as a multi-step process that includes modeling, role-playing, and practice (Task V.B.4: "Teach skills using evidence-based methods"). The standard sequence is to first describe the skill, then model it (demonstrate how it is performed), followed by role-playing (where the individual practices in a simulated setting), and finally real-world practice. Option A (modeling the skill) aligns with this, as role-playing typically follows modeling to allow the individual to observe the skill in action before attempting it themselves in a controlled, supportive environment.

Option B (practicing the skill) refers to real-world application, which comes after role-playing. Option C (trying the skill for the first time) is vague but implies initial practice, which role-playing itself facilitates. Option D (describing how to do the skill) precedes modeling, as description alone is insufficient before demonstration. The PRA Study Guide, referencing skill-teaching models like the Boston University Psychiatric Rehabilitation approach, confirms that role-playing follows modeling, supporting Option A.

A man with a psychiatric disability continues to be fearful of connecting with others even after significant reduction in his symptoms and completing interpersonal skills training. The next step for the practitioner is to:

Assess his experience with trauma.

Stress the importance of strengthening his relationships.

Review his lack of motivation to change.

Request a change in his current medication.

This question aligns with Domain IV: Assessment, Planning, and Outcomes, which focuses on reassessing individuals’ needs when progress stalls to identify underlying barriers. The CPRP Exam Blueprint emphasizes “conducting assessments to identify factors, such as trauma, that may impact recovery goals, particularly when expected progress is not achieved.” The individual’s persistent fear of connecting with others, despite reduced symptoms and skills training, suggests a potential underlying issue, such as trauma, that requires further assessment.

Option A: Assessing the individual’s experience with trauma is the best next step, as trauma can cause persistent fear of social connection, even after symptom reduction and skills training. This assessment ensures the practitioner understands the root cause and can tailor interventions, aligning with person-centered planning.

Option B: Stressing the importance of relationships may pressure the individual without addressing the underlying fear, which could be counterproductive and non-therapeutic.

Option C: Reviewing motivation assumes the issue is a lack of effort, which is premature and dismissive without first exploring potential barriers like trauma.

Option D: Requesting a medication change assumes a pharmacological issue without evidence, ignoring the need to assess non-symptom-related barriers like trauma.

Extract from CPRP Exam Blueprint (Domain IV: Assessment, Planning, and Outcomes):

“Tasks include: 1. Conducting assessments to identify barriers to progress, including trauma or other psychosocial factors. 4. Revising rehabilitation plans based on reassessment findings to address underlying issues.”

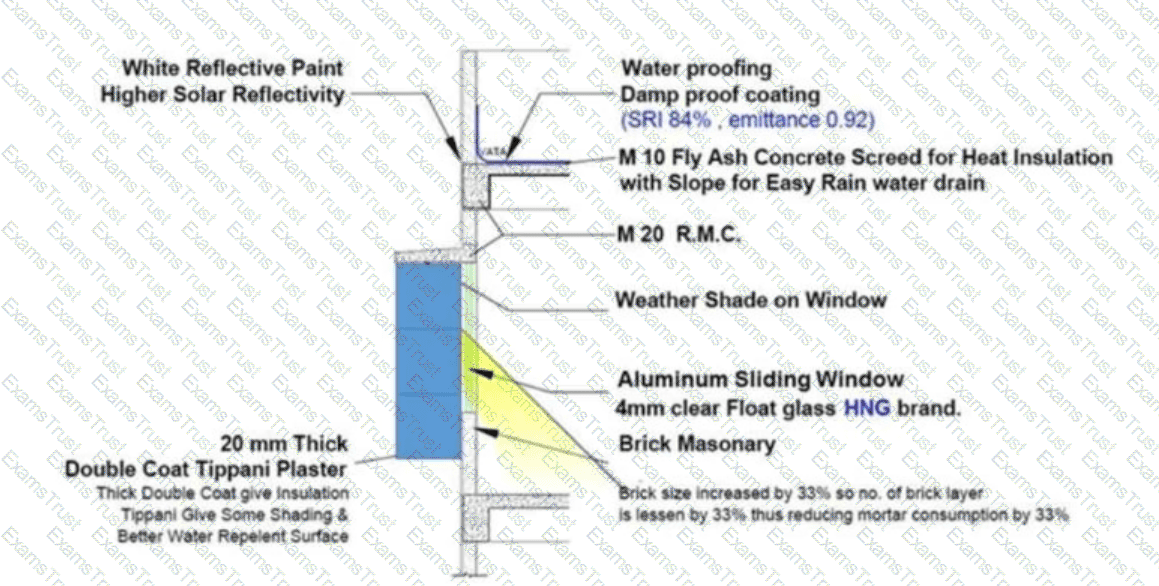

The detail below is presented by the client.

What strategy is good for embodied energy saving?

External shading

Fly ash concrete

Aluminum sliding window

Waterproofing with SRI of 84%

Embodied energy refers to the total energy consumed in the production, transportation, and installation of building materials, a key consideration for sustainable design that supports health and wellness through environmentally responsible practices. The CPRP Exam Blueprint (Domain VII: Supporting Health & Wellness) indirectly relates to this through promoting wellness via sustainable, health-focused environments (Task VII.A.1: "Promote holistic wellness, including purpose and meaning in life"). Option B (fly ash concrete) is the best strategy for embodied energy saving, as fly ash—a byproduct of coal combustion—replaces a portion of Portland cement in concrete, which has high embodied energy due to its energy-intensive production (e.g., 4,000–5,000 MJ/ton for cement vs. 800–1,000 MJ/ton for fly ash concrete). Using fly ash reduces energy consumption, lowers greenhouse gas emissions, and enhances concrete durability, aligning with sustainable practices that support wellness by reducing environmental impact.

Option A (external shading) reduces operational energy (e.g., cooling) but has minimal impact on embodied energy, as shading materials (e.g., louvers) still require production energy. Option C (aluminum sliding window) has high embodied energy, as aluminum production is energy-intensive (around 200 MJ/kg). Option D (waterproofing with SRI of 84%) focuses on solar reflectance to reduce heat gain, affecting operational energy, not embodied energy, and waterproofing materials (e.g., coatings) have moderate production energy. Literature on sustainable construction, such as guidelines from the U.S. Green Building Council, emphasizes fly ash concrete for embodied energy savings, supporting Option B.

Which of the following strategies is most important for practitioners to use in order to help individuals move forward?

Basic listening skills

Reflecting on emotions

Problem-solving processes

Individualized teaching techniques

Helping individuals move forward in recovery requires establishing a foundation of trust and understanding. The CPRP Exam Blueprint (Domain I: Interpersonal Competencies) identifies basic listening skills as the most critical strategy for engaging individuals, as they enable practitioners to understand needs, build rapport, and foster collaboration (Task I.B.3: "Adapt communication strategies to build trust and engagement"). Option A (basic listening skills) aligns with this, as active listening—attending, paraphrasing, and clarifying—creates a safe space for individuals to express goals and challenges, driving progress.

Option B (reflecting on emotions) is a component of listening but narrower. Option C (problem-solving processes) is action-oriented and secondary to understanding. Option D (individualized teaching) is relevant for skill-building but not the foundation for moving forward. The PRA Study Guide emphasizes listening as the primary engagement strategy, supporting Option A.

During a discussion with his practitioner, an individual reports that a recently formed relationship has helped him feel better in general. This is an example of

independent living.

friendship as a component of a healthy lifestyle.

co-dependence.

positive reinforcement contributing to a healthy lifestyle.

Social relationships are a key component of health and wellness in psychiatric rehabilitation, contributing to emotional well-being and recovery. The CPRP Exam Blueprint (Domain VII: Supporting Health & Wellness) emphasizes promoting social connections as part of a healthy lifestyle (Task VII.B.1: "Support the development of social and interpersonal skills"). Option B (friendship as a component of a healthy lifestyle) directly aligns with this task, as the individual’s new relationship is described as improving his general well-being, reflecting the positive impact of social support and friendship on mental and emotional health.

Option A (independent living) relates to community integration (Domain III) but does not specifically address the emotional benefits of relationships. Option C (co-dependence) is incorrect, as the question does not suggest an unhealthy reliance on the relationship, and co-dependence is not a recovery-oriented concept. Option D (positive reinforcement contributing to a healthy lifestyle) is less precise, as the relationship itself is the direct contributor to well-being, not an external reinforcement mechanism. The PRA Study Guide highlights social relationships as a pillar of wellness, supporting Option B.

Which of the following impacts a person’s ability to become engaged in her communities?

Treatment compliance

Degree of opportunity

Past successes

Diagnosis

Community engagement depends on access to opportunities that allow individuals to participate in meaningful roles, such as employment, volunteering, or social activities. The CPRP Exam Blueprint (Domain III: Community Integration) emphasizes that the degree of opportunity—access to resources, inclusive environments, and community activities—directly impacts an individual’s ability to engage in their communities (Task III.B.1: "Identify and address barriers to community participation"). Option B (degree of opportunity) aligns with this, as structural and social opportunities (e.g., accessible programs, welcoming community spaces) are critical drivers of community integration.

Option A (treatment compliance) may support stability but is not the primary factor for community engagement. Option C (past successes) influences confidence but is less direct than access to opportunities. Option D (diagnosis) is a clinical factor that does not inherently determine community participation, which is more about external opportunities and supports. The PRA Study Guide highlights opportunity access as a key facilitator of community integration, supporting Option B.

Effective programmatic level strategies for addressing comorbidity include the integration of

alternative treatments.

mental and physical health services.

group social activities.

dual recovery and spiritual services.

Comorbidity, particularly the co-occurrence of mental health and physical health conditions, requires integrated service delivery to address complex needs effectively. The CPRP Exam Blueprint (Domain VI: Systems Competencies) emphasizes the development of integrated service systems to address co-occurring disorders (Task VI.B.2: "Promote integration of mental health, physical health, and substance use services"). Option B (mental and physical health services) aligns with this, as integrating these services ensures holistic care, addressing both psychiatric symptoms and physical health issues (e.g., metabolic syndrome from antipsychotics) through coordinated care plans, shared records, and interdisciplinary collaboration.

Option A (alternative treatments) is vague and not a primary strategy for comorbidity, as it lacks specificity and evidence-based support. Option C (group social activities) supports wellness but does not directly address comorbidity’s clinical needs. Option D (dual recovery and spiritual services) is relevant for substance use and mental health comorbidity but is narrower than Option B, which encompasses a broader range of physical health issues. The PRA Study Guide highlights integrated care models as best practice for comorbidity, supporting Option B.

An individual is working on setting an overall rehabilitation plan with her practitioner. One of the objectives is to return to college to finish her degree in accounting, but she wants to work on other objectives first. This person is MOST likely in what stage of change?

Acceptance.

Action.

Contemplation.

Maintenance.

The Stages of Change model guides the development of rehabilitation plans by assessing an individual’s readiness to pursue specific goals. The CPRP Exam Blueprint (Domain IV: Assessment, Planning, and Outcomes) emphasizes evaluating stages of change to prioritize goals in person-centered planning (Task IV.A.2: "Assess individual’s stage of change and readiness for goal-setting"). Option C (Contemplation) aligns with this, as the individual is considering returning to college (indicating awareness of the goal) but prioritizes other objectives first, suggesting she is not yet ready to act on the college goal but is weighing its importance.

Option A (Acceptance) is not a stage of change, though it may describe an attitude in later stages. Option B (Action) involves actively pursuing a goal, which does not match the individual’s focus on other objectives. Option D (Maintenance) applies to sustaining changes already made, not planning future goals. The PRA Study Guide describes contemplation as the stage where individuals are aware of a goal but not yet committed to action, supporting Option C.

An individual's treatment team is divided regarding her decision to work a full-time job. Part of the team is supportive of the idea. Others feel that the stress will be too much and will cause her to become symptomatic. The IPS model of supported employment would encourage the practitioner to assist her with

integrating her vocational and mental health services.

developing strong natural supports before moving forward.

improving her symptom management skills prior to getting a job.

determining appropriate vocational and treatment goals.

The Individual Placement and Support (IPS) model of supported employment is an evidence-based approach that emphasizes rapid job placement and integrated support for individuals with mental health conditions. The CPRP Exam Blueprint (Domain III: Community Integration) highlights the IPS principle of integrating vocational and mental health services to support employment goals (Task III.A.3: "Support individuals in pursuing self-directed community activities, including employment"). Option A (integrating her vocational and mental health services) aligns with this, as IPS encourages close collaboration between employment specialists and mental health providers to provide seamless support, such as on-the-job coaching and mental health interventions, to help the individual manage stress and succeed in her full-time job despite team concerns.

Option B (developing natural supports) is valuable but not a core IPS principle, which prioritizes rapid placement over prerequisite conditions. Option C (improving symptom management skills prior) contradicts IPS’s focus on immediate job placement rather than pre-employment skill-building. Option D (determining vocational and treatment goals) is part of planning but less specific than integration, which addresses the team’s concerns directly. The PRA Study Guide and IPS guidelines emphasize integrated services as central to supported employment, supporting Option A.

Which of the following is included when assessing an individual’s rehabilitation readiness?

Assessing the individual’s strengths and weaknesses

Establishing connections with the individual and others

Identifying the desire to change at this time

Identifying potential resources for rehabilitation

Rehabilitation readiness assessment evaluates an individual’s preparedness to engage in recovery-oriented goal-setting and activities. The CPRP Exam Blueprint (Domain IV: Assessment, Planning, and Outcomes) specifies that assessing readiness includes identifying the individual’s desire and motivation to change, as this drives their willingness to pursue goals (Task IV.A.2: "Assess individual’s stage of change and readiness for goal-setting"). Option C (identifying the desire to change at this time) aligns with this, as it focuses on the individual’s current motivation and commitment, a key component of readiness often assessed through tools like the Stages of Change model.

Option A (assessing strengths and weaknesses) is part of a functional assessment, not specifically readiness. Option B (establishing connections) relates to engagement (Domain I), not readiness assessment. Option D (identifying resources) is part of resource assessment, not readiness. The PRA Study Guide emphasizes motivation and desire to change as central to readiness assessment, supporting Option C.

What statement is the best example of an objective that is measurable and addresses observable behavior? The individual will:

Increase medication compliance to 100%.

Arrive to work on time four out of five days per week.

Increase use of social skills related to living environments.

Learn to seek help more often within the next six to eight weeks.

This question aligns with Domain IV: Assessment, Planning, and Outcomes, which focuses on developing measurable, observable objectives in rehabilitation plans. The CPRP Exam Blueprint emphasizes that objectives should be “specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART), with a focus on observable behaviors to track progress.” The question tests the ability to identify an objective that is both measurable and tied to observable actions.

Option B: “Arrive to work on time four out of five days per week” is specific, measurable (four out of five days), observable (on-time arrival), and time-bound (weekly). It meets SMART criteria and allows clear tracking of progress, making it the best example.

Option A: “Increase medication compliance to 100%” is measurable but lacks specificity (e.g., timeframe or method of measurement) and may not be fully observable without detailed monitoring, making it less precise than Option B.

Option C: “Increase use of social skills related to living environments” is vague, as “social skills” and “increase” are not clearly defined or measurable, and the behavior is not easily observable without specific criteria.

Option D: “Learn to seek help more often within the next six to eight weeks” is not sufficiently measurable (e.g., what constitutes “more often”?) and lacks clarity in observing the behavior, making it less effective as an objective.

Extract from CPRP Exam Blueprint (Domain IV: Assessment, Planning, and Outcomes):

“Tasks include: 4. Developing rehabilitation objectives that are specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound. 5. Focusing on observable behaviors to evaluate progress toward objectives.”

An individual is enduring a prolonged exacerbation of negative symptoms of schizophrenia. The symptoms seem to worsen in the middle of the night when very few supports are available. The BEST approach is to

practice self-management techniques.

visit your nearest crisis response clinic.

call the Warm-Line.

take melatonin at bedtime.

Negative symptoms of schizophrenia, such as social withdrawal or apathy, can intensify during low-support periods like nighttime, requiring accessible, non-clinical support options. The CPRP Exam Blueprint (Domain VII: Supporting Health & Wellness) emphasizes connecting individuals to peer-based supports to manage symptoms and enhance wellness (Task VII.B.2: "Promote access to peer support services"). Option C (call the Warm-Line) aligns with this, as Warm-Lines are peer-operated, non-crisis phone services that provide emotional support, coping strategies, and connection during difficult times, ideal for nighttime when other supports are unavailable.

Option A (practice self-management techniques) is valuable but may be challenging during an exacerbation without guidance. Option B (visit a crisis clinic) is inappropriate, as negative symptoms do not typically warrant crisis intervention. Option D (take melatonin) addresses sleep but not the emotional or social impact of negative symptoms. The PRA Study Guide highlights Warm-Lines as effective for non-crisis support, supporting Option C.

An individual with a history of substance abuse and problems with anger management has been living with his family for the last four years. His parents told him that he must stop using drugs or move out. When discussing his situation with the practitioner, the individual becomes angry and threatens that he will hurt his family. What is the best initial action for the practitioner?

Determine the level of risk in this situation

Provide a quiet environment to speak with the individual

Judge the individual’s level of emotional upset

Encourage the individual to calm down

When an individual makes a threat of harm, the practitioner must prioritize safety through a structured risk assessment. The CPRP Exam Blueprint (Domain I: Interpersonal Competencies) emphasizes assessing risk to ensure safety for the individual and others when threats are expressed (Task I.C.1: "Assess and respond to safety concerns in a trauma-informed manner"). Option A (determine the level of risk in this situation) aligns with this, as it involves evaluating the seriousness, intent, and means of the threat to guide immediate actions, such as de-escalation or referral to crisis services, protecting the family and individual.

Option B (provide a quiet environment) may be a follow-up but is not the initial priority over safety. Option C (judge emotional upset) is vague and less actionable than risk assessment. Option D (encourage calming down) risks escalating the situation without assessing risk. The PRA Study Guide underscores risk assessment as the first step in managing threats, supporting Option A.

What are the four most important factors that support recovery in psychiatric rehabilitation?

Family, home, resilience, and work

Health, home, hope, and relationships

Family, community, religion, and relationships

Health, home, community, and purpose

Recovery in psychiatric rehabilitation is supported by holistic factors that foster well-being and empowerment. The CPRP Exam Blueprint (Domain V: Strategies for Facilitating Recovery) emphasizes key recovery pillars, including health (physical and mental wellness), home (stable housing), hope (motivation and optimism), and relationships (social support), as critical for sustained recovery (Task V.A.1: "Promote recovery principles, including self-determination and satisfaction"). Option B (health, home, hope, and relationships) aligns with this, reflecting SAMHSA’s recovery framework, which prioritizes these elements as foundational for individuals to achieve meaningful lives.

Option A (family, home, resilience, work) is close but less comprehensive, as resilience is an outcome and work is a specific goal. Option C (family, community, religion, relationships) is too narrow, as religion is not universal. Option D (health, home, community, purpose) omits hope, a critical motivator. The PRA Study Guide aligns with SAMHSA’s recovery factors, supporting Option B.

Copyright © 2014-2026 Examstrust. All Rights Reserved